Val Lewton was responsible for producing a slate of psychological horror pictures for RKO studios in the days following the financial disaster which incurred after Orson Welles' Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons almost bankrupted the studio. Lewton had worked for David O. Selznick as a story editor and yearned to be his own master ... write his own stories and produce his own motion pictures. RKO made his dream come true. With the release of, Cat People, a low budget picture that implied horror ... not show it, Lewton was on his way to imprint his influential style on celluloid and in the minds of future directors and producers. After Cat People, eight more films rolled out of the RKO Studio gates and into theaters.

Val Lewton was responsible for producing a slate of psychological horror pictures for RKO studios in the days following the financial disaster which incurred after Orson Welles' Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons almost bankrupted the studio. Lewton had worked for David O. Selznick as a story editor and yearned to be his own master ... write his own stories and produce his own motion pictures. RKO made his dream come true. With the release of, Cat People, a low budget picture that implied horror ... not show it, Lewton was on his way to imprint his influential style on celluloid and in the minds of future directors and producers. After Cat People, eight more films rolled out of the RKO Studio gates and into theaters.A few years ago, a dvd box set of Lewton produced films was released. I was lucky enough to purchase this treasure trove of film history and recently decided to run my greedy hands through the jewels inside. The first gem I decided to examine was The Seventh Victim. I had heard that this was the most obscure and most bizarre of his films. I was intrigued and curious ... and I was quite pleased with what I eventually viewed.

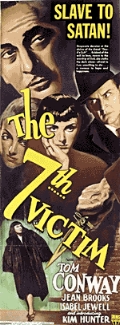

Lewton produced The Seventh Victim, but it was directed by a protege of his named Mark Robson. Made in 1943, the film blends the film noir technique of shadows, dark corners, fedora wearing silhouettes, jagged lines of light and dark and that ever present mood of impending doom with that of the standard noir film. His films insinuated horror and monstrous acts and much evil was done off-screen. There are moments of footsteps being heard behind a frightened protagonist, dark looks that betray horrible sick thoughts and the nuances of film creativity. Many times his style was to use the dark and the wonderful tool of sound to create pure utter fright.

Val Lewton

Much of the horror portrayed on screen in the 1930s and 1940s was located in some bizarre mix of German/English/Romanian country populated with American and English actors battling man-made monsters, vampires and lupine man-beasts. These were being produced at RKO's rival low budget studio Universal Pictures. Lewton's horror was more familiar. His was not the fright of the creature pouncing at you from the darkened room, but the horror of what your own mind could produce from what he implied through shadows, light and simple sound. Most of these was done due to budget restraints, but it proves to be more frightening and more real. And his locations were right here in America ... in this case, New York City, to be specific, Greenwich Village.

The story begins as the virginal simple Mary Gibson must leave the safety of her Victorian-like girls' school and travel to Manhattan in search of her missing sister Jacqueline. Jacqueline was funding Mary's cloistered education and without the funds that her wealthy sister provides, explains her stiffly starched headmaster, Mary will have to leave the school. She does, but to find Jacqueline and solve the mystery of her disappearance. Along the way, much like a fairy tale Goldilocks, Mary encounters, instead of bears, three men; Jacqueline's lawyer husband who begins to fall in love with Mary, a love-sick poet who lives above the Dante Restaurant and harbors his own love for Mary and a smarmy cultured psychiatrist with the cliche noir smoldering cigarette in his two fingers, a pencil moustache and English accent. This man knows more than he should and with his help and that of other two gentlemen, Mary eventually learns of her sister's whereabouts. Those whereabouts involve a devil cult, located in arty Greenwich Village, who will stop at nothing, including murder, to keep their secrets. Their willingness to kill Jacqueline may just be in competition with her own pessimistic attitude toward her own life and the ending of it. Lewton described the theme of this film as "Death is good."

The film is filled with fantastic shots of characters bathed in shadows. An undercurrent of sexuality is running through the story; both hetero and homosexuality. The sense of lesbianism is subtle, but evident by the acting style of the strong women and their meek submissive counterparts. Mary seems quite young (her school appears to be populated by older teens) and the sexual attraction the older men in the film have for her is a bit uncomfortable. Mary is like the pure white lamb wandering from her flock into a den of wolves. Every character seems surrounded by gloom, even supporting characters portraying secretaries and penny-ante private detectives. A standout scene is one in which Mary is returning home at night after seeing a murder and runs aboard a underpopulated subway car. As she sits there in fright, two men enter, both dressed as if they had had a night out on the town; one in top hat, in fact. They are supporting a, presumed, drunken third companion. Mary senses something wrong and she is correct. In her unease she gets up to find refuge in the next car. As she turns to look back at the men, two of them stare at her with obvious knowing menace. It is truly scary.

3 comments:

this sounds so good! a well-written post, indeed.

Nice, blog. I have never actually seen this. I don't think I was a huge fan of Cat People when I saw it. I'm more in the Universal/ James Whale lot. But this does sound interesting. I love the quote "Death is good."

La muerte no es buena para la salud

Post a Comment